The Beccles Society - An Article On The Rich

The Rich

It was rather dangerous being an aristocrat, especially a Duke during the 15th century. The history of the family of the Dukes of Suffolk is an extreme example;

William de la Pole was created Duke of Suffolk, his grandfather was forced to flee the country and died in France, his father died of dysentery at Harfleur on the way to the Battle of Agincourt, of his brothers, the eldest son Michael was killed at the Battle of Agincourt, Alexander was killed in the Battle of Jargeau, John died as a prisoner of the French, Thomas died in France as a hostage.

William was appointed Chancellor and created Duke of Suffolk in 1448 for the support he had given to the unpopular and at times deranged King Henry VI, who was more interested in founding and building colleges, such as Eton College and Kings College Cambridge than keeping the nobility under proper discipline. Suffolk became unpopular with Parliament, was charged with embezzlement and negligence in allowing the army to be defeated by Joan of Arc. In January 1450 he was arrested, imprisoned in the Tower and impeached by parliament. Henry VI intervened to protect him, he was banished for five years, but on his crossing to Calais his ship was intercepted and he was captured, subjected to a mock trial, and beheaded

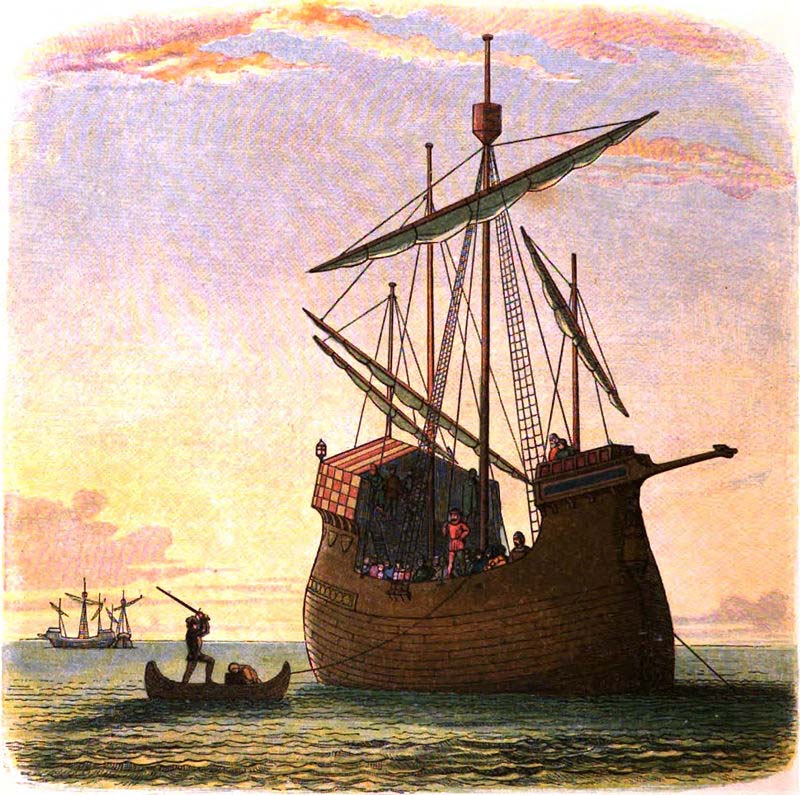

The murder at sea in 1450 of William de la Pole the first Duke of Suffolk; (19th century illustration from "A Chronicle of England")

His son, John de la Pole, 2nd Duke spent much of his time in Norfolk engaged in disputes with his neighbours including John Paston II. He married the sister of the future King Edward IV and participated in some of the Battles of the Wars of the Roses, during which Henry VI was deposed by Edward IV. Henry was subsequently returned to power, was then defeated and finally murdered in the Tower, Meanwhile the Duke being very poor for a Duke avoided attending court functions, where his income was too small to support a suitable retinue, managed to keep his head through five turbulent reigns and died in 1492 at home and was buried under a magnificent memorial in Wingfield church – the only member of the family to die peacefully at home.

Wingfield Church: View of the Sanctuary with the tomb of the second Duke of Suffolk on the south side

Tomb of John de la Pole 2nd Duke of Suffolk, died 1492, and his wife Elizabeth in Wingfield Church

Of two of his sons, John the elder joined the rebellion of Perkin Warbeck and was killed at the Battle of Stoke, while the Dukedom descended to Edmund who became pretender to the throne of England through his mother, fled to Germany to the Court of the Emperor Maximilian, whose son, Philip agreed to hand him over to Henry VII on the undertaking that he would not be harmed. Unharmed, he was kept in prison. Henry VIII however had not made any such promise so Suffolk was beheaded in 1513. The youngest son Richard escaped to France declared himself Pretender to the throne but was killed at the battle of Pavia in 1525. That was the end of the main male line of the de la Pole family.

This carnage shows the violence of the Middle Ages, especially during this period. There is also the international aspect of the deaths; some were killed in England, others in France, one on the high seas and one in Italy. Despite the size of the families they were wiped out in the male line. It was not all that safe being a monarch either, William II may have been murdered, Edward II, Richard II, Henry VI, and the Princes in the Tower, were murdered, Richard III died in the battle of Bosworth, Mary Queen of Scots was executed, and finally Charles I was also executed. Many of those who had either a close or distant claim to the throne were disposed of by their cousin, the monarch, in one way or another.

The wars were concerned with either, the claim by English Kings to provinces in France, the annexation of the countries of Wales and Ireland and the pacification of the Scottish border, or the dynastic claims of one member of the royal family against the present king. Only a couple of affrays were connected to the welfare of the people, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 which was subdued by a subterfuge and Kett’s Rebellion in 1549 centred on Norwich, which was routed by a well-trained army mostly of mercenaries under the Earl of Warwick.

JOHN PASTON I

John Paston, born in 1421, was the eldest son and heir of William Paston, Justice of the Common Pleas. He was educated at Cambridge and like his father, became a lawyer.

Much more is known about the Pastons than any other gentry family in the medieval period on account of the preservation of letters that were exchanged amongst the family.

The Pastons were the victims of the rivalry for power and status in East Anglia between the 3rd Duke of Norfolk and the first Duke of Suffolk. Suffolk’s followers terrorised their neighbours including the Pastons’ taking their Manor of East Beckham and claiming the Manor of Gresham, damaging the house and forcing Margaret Paston to leave. After the fall of Suffolk three years later in 1450 they recovered the Manor of Gresham. In 1455 Paston was elected as one of the Knights of the Shire for Norfolk, but did not take a seat in Parliament as this time it was the Duke of Norfolk who "insisted on his own nominees being returned". – Modern corruption of power seems slight in comparison!

Sir John Fastolf was a relative of Margaret Paston’s, a soldier who had fought at Agincourt, was wealthy and childless. Paston was appointed as one of the ten Feoffees of his lands.

After Fastolf died Paston claimed that Fastolf had made a nuncupative will giving Paston exclusive authority over the foundation of a college, and providing that, after payment of 4000 marks, Paston was to have all Fastolf's lands in Norfolk and Suffolk.

Relying on the nuncupative will, Paston took possession of the Fastolf estates, and resided at times at Fastolf's manors of Caister and Hellesdon.

For the rest of his life and much of the life of his sons the Pastons spent their time trying to retain their possessions in the courts and by defending themselves from attacks by force.

Subsequently John Paston I spent three periods in the Fleet Prison accused of trespassing on the lands he claimed.

In the hotbed of financial rivalry and rapacity in Norfolk it seems difficult to sustain a claim made in a nuncupative will by Falstoff two days before his death. It is unclear whether it was even witnessed.

On the death in London of John Paston in 1466 his body was accompanied from London to Norfolk by a priest & 12 poor men carrying torches. It lay in St Peter Hungate, overnight, surrounded by 38 priests, 39 choir boys, 26 clerks, 4 torch bearers, the Prioress of Carlow & the anchoress of her house. £50 in gold & silver was distributed as alms at the funeral.

In today’s value that £50 might be worth about £300,000. They were not short of cash

I cannot find any family in Beccles before the 16th century with sufficient biographical information to use as a local example. So I have chosen to track the Rede family from the 14th century long before they reached Beccles.

If Burke’s Peerage is correct, the family’s origins were well established by 1396 when John Rede was appointed a Sergeant at Law, a small, elite group of lawyers who took much of the work in the central common law courts. Many of the family varied in their professions between merchant and lawyer. In fact John’s grandson, another John Rede was a merchant of Norwich and an Alderman becoming Mayor of the city in 1496. It is his tomb which now stands in the Chancel of St Michael’s Church to the north of the altar in the Sanctuary.

He had two sons living in Beccles one of whom was Rector of the town. He and his wife probably chose to move here in their seventies for that reason.

His will gives us a clear indication of his wealth. He left £8 or £9 for his gravestone, which turns out to be the elaborately carved tomb-chest just mentioned. He left a large sum to charity amounting to £162 over a period of six years. This was to go to the poor of Beccles and 26 villages round.

Another £83 was to go to the friaries of Norwich and Yarmouth over six years This was not quite the end of charitable work, for he gave to the sick folks about Norwich gates £2 and Beccles Hospital 12shillings over 6 years.

When his wife Joan died in 1519 she left money to the Friars of Norwich, Yarmouth and Gorleston and to the nuns of Norwich Hospital in Yarmouth besides the Prisoners of Norwich Castle to whom she gave 4d a week in milk and bread "as long to continue as £2 will last". This sort of charity was fairly common as prisoners were incarcerated but they had to pay for food, and if they had no money that was hard.

She also left some money "to the way from Ingate Church to the town of Beccles". Ingate Church was at the junction of Derby Road and Kemp’s Lane on the northern side. It was pulled down at the orders of Queen Elizabeth in 1588 and the money from the sale of the fabric etc was given for the relief of Dunwich. - I wonder what the people of Beccles thought about that? This was common practise with the Tudors, giving money which wasn’t theirs to another person or organisation as a gift.

The Executor was to be : "My beloved son and trusty friend my eldest son William Rede."

We will deal with him next

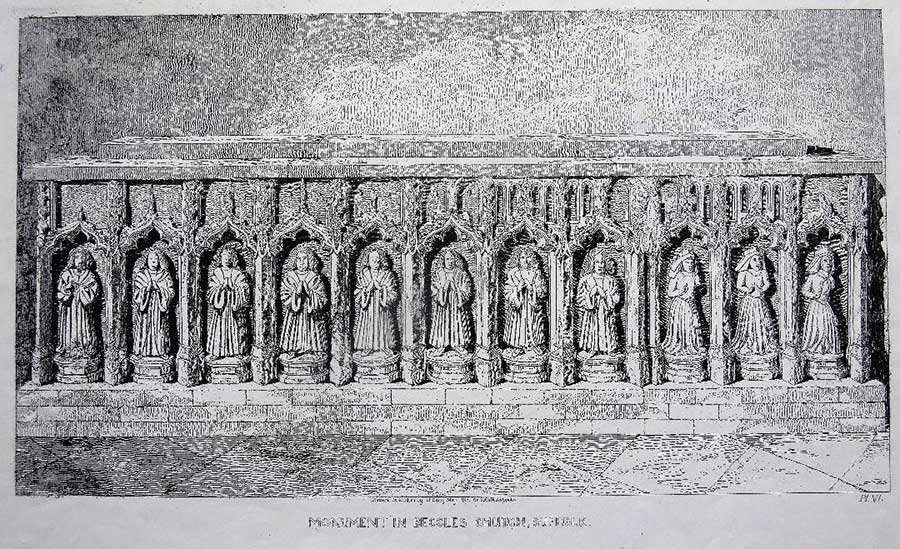

The tomb of John Rede 1500 in St Michael’s Church, Beccles. Engraving by Henry Davey 1818 showing Rede's eleven children as "weepers"

Photograph of the tomb of John Rede, 1500, in St Michael’s Church Beccles. Only 10 weepers can be seen. Is the other one embedded in the wall?

William Rede I, gentleman was the richest man in Beccles by a long way. He was the second richest commoner in Suffolk after Spring, the clothier, of Lavenham. The valuation of his goods was £466. The next wealthiest in Becles was Thomas Garneys, Esquire: £50 in land, the ancestral owner of Roos Hall. Despite his money Rede is not listed as an esquire. It was a rank in society. The total value of Beccles in goods wages land and stock in 1524 was £1781 amongst 307 people, but William Rede was worth between a third and a quarter of the total worth of the town.

In November 1539 Henry VIII through his Commissioners took over Bury Abbey. He also took over Beccles Fen & Common. The chief man in the town was William Rede I, a mercer and merchant, "a man of worship", a justice of the Peace for Suffolk, "one specially beloved & trusted, that did give great alms to the poor and did bestow good sums of money in mending of highways about & near the town." He was an elderly man. William Reed was given the job of buying the fen from the king. Altogether William Rede had a total of £300 - £400 from the town at his disposal.

"Merchant Rede, with the Abbot's grant and the money in his saddle bag, took horse for London. He had his instructions, - to buy the Fen, on the best terms he could, and obtain the land for the town, which had become so essential for its prosperity. At the same time William Rede I's younger son William II was attempting to purchase the manor of Beccles, but was told he should not try to buy the manor until his father had obtained the Fen.

William Rede I - said the inhabitants were very poor , but that HE had money, and was willing to pay off £6 of the rent of £6-13-4 at 20 years purchase (which is what the Court of Augmentations was asking), or £120 - leaving 13s-4d as a perpetual ground rent to the Crown. - William Rede I was given the Grant. From the £350 or more at his disposal Rede had paid £120 & his expenses. He appeared to have pocketed the rest. The result of this was that the Redes and the Town were in conflict for the next 60 years, some supported the Redes, but it seems that most were opposed to them.

Waveney House Hotel today: William Rede I, son of John, owned the site of this house before 1550

WILLIAM REDE II

He was born in Beccles in 1513 He married Ann Fearnly of Creeting in 1538. They had one surviving son William Rede born in 1538. He was a successful merchant based in London, whereas his forebears had been working in East Anglia. While his father was buying the Fen of Beccles for the people of Beccles, he was buying the Manor of Beccles, as its fist secular landlord. He only held it for a couple of years before his premature death.

He died in London at the age of 29 in 1542. He had inherited a considerable amount of his father‘s estate.

Ann his widow married, after his death, one of the wealthiest and most influential people in the country Sir Thomas Gresham.

Gresham had been concerned with restoring the value of the pound after its debasement in the reign of Henry VIII, besides being the country’s representative in Rotterdam and building the first Royal Exchange in London. He was important n developing London as a financial centre and he personally owned 24 Manors in the country.

William Rede III born in London in 1538 received a good portion of his grandfather’s wealth, but much of Gresham’s riches as well, so he was exceptionally rich. He carried on the vendetta between the Redes and the town of Beccles through the Courts, but was unconcerned with the relatively large expense of these legal actions. However it had a much greater effect on the finances of the town. He built himself a large house at Syon just outside London which was subsequently updated by Robert Adam in the late 18th century and remains one of Adam’s most acclaimed interior designs.

He married Gertrude Paston, great-grand-daughter of John Paston III and they had one daughter who married Sir Michael Stanhope of Sudbourne, Suffolk (an MP) and whose large tomb is in the sanctuary of the church with an effigy of him wearing armour.

They had 3 daughters two of whom married into the aristocracy: Jane married Sir William Withepoll, whose daughter married 6th Viscount Hereford. Elizabeth married George 8th Baron Berkeley, and Bridget married George 1st Earl of Desmond, who she divorced 5 years later. It was difficult for anyone to obtain a divorce in 1630, but somehow it happened. He had children with a second wife.

So eventually William Rede’s and Sir Thomas Gresham’s riches were absorbed by the nobility.

300 Years Later:

The “Return of Land” survey of 1873 shows that four-fifths of the land in Britain was owned by less than 7000 people out of a population of about 31 million. In England 360 people had estates of 10,000 acres, perhaps two thirds of whom were members of the aristocracy.

The 1,000 greater gentry had estates of 3000 to 10,000 acres.

This included the Worlingham Estate of Sir Charles Clarke of 3,046 acres, but smaller than it had been when Robert Sparrow owned it earlier in the century.

The Benacre Estate of the Gooch family was 7186 acres; but they were also major land owners in Birmingham.

The 2000 squires had estates between 1 and 3,000 acres, this included the Ringsfield Estate of John Garden of 1845 acres.

Trollope’s Archdeacon Grantly states: “Land gives so much more than rent. It gives position and influence and political power.” This remained true until the end of the century, or perhaps until Lloyd George’s Budget of 1910, which imposed a 20% tax on the increase in the value of land, payable on death or the sale of land, a rise in income tax, and supertax on very high incomes. This was to pay for the new welfare programmes such as the introduction of old age pensions as well as battleships for the navy. This marked the beginning of the end of the hold on power of the aristocracy and gentry.”

It is interesting to consider our own reactions today more than a century later. The National Trust’s collection of magnificent houses and other stately homes open to the public complete with accompanying booklets showing not only photographs of the architectural grandeur of the exterior of these houses and their sumptuous interiors, but also family trees to show the line of descent of their owners with brief biographies, proves that many people have a fascination with and admiration for the riches and power of these very wealthy families of the past. The response is not just aesthetic pleasure at looking at an Adam ceiling or fireplace, nor one of envy at the lavishness of the display, but a sense of wonder and some regret at its passing.

The Crossleys of Halifax and Somerleyton in Suffolk

The rich were not always from privileged backgrounds, The Crossleys were self-made. Their fortune was based on carpets.

Mark Girouard describes them brilliantly in his book the Victorian Country House:

One narrow valley in Halifax chocked with Crossley mills (covering 20 acres) paid for the Crossley orphanage (an immense structure), the Crossley almshouses, the Crossley Chapel (they were non-conformists), Crossley Street, the Crossley Hotel, the Crossley baths, the Crossley Park, Crossley model housing and a ring of the Crossley’s own houses. Crossleys contributed to every conceivable charity. They were Liberal MPs and Mayors of Halifax.

They were the first carpet manufacturers to harness the steam engine to the production of carpets and they became the largest manufacturers in the world and cutting the cost by weaving six times faster than the hand loom. Manufacturers of tapestry and Brussels carpets applied to Messrs. Crossley for licences to work their patents, and large sums accrued to them from royalties alone.

They employed 6,000 people. In 1864 the concern was changed into a limited liability company, and a portion of the shares in the new company was offered to workers under favourable conditions.

Sir Francis Crossley bought Somerleyton from another great industrialist Sir Morton Peto. More of him later.

All Francis Crossley’s roots were in Halifax, but it was probably his wife who came from Kidderminster, daughter of a well-known carpet manufacturer, who disliked Yorkshire and their comparatively modest house in Halifax built between the cemetery and a public park, wanted a larger house in a rural area and chose Suffolk. Their son Savil went to Eton and became Conservative MP for North Suffolk and the first Baron Somerleyton.

The Estate is of 5000 acres remains in the ownership of the 4th Baronet Crossley.

It had been owned previously by two other Baronets of different families, first was:

Admiral Sir Thomas Allin, 1st Baronet

Thomas Allin was born in 1612, the son of Robert Allin. He lived in Lowestoft for the first part of his life, where he was a merchant and ship-owner. On the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, Allin sided with the Royalists, in common with most of the town. He played a significant part in the subsequent privateering operations against Lowestoft's Parliamentarian rivals at Great Yarmouth, and eventually transferred his operations to the Netherlands for greater security. He remained in the service of Prince Rupert of the Rhine in the exiled royalist fleet after the Civil War. He commanded the Royalists' Charles in 1648 Allin was rewarded for his loyalty to the monarchy after the English Restoration by being given command of various vessels and during 1663 he was made Commander-in-Chief, with the rank of commodore.

In 1664 Allin was nominated to succeed Sir John Lawson as commander in the Mediterranean

Allin returned to England in the spring of 1665, and took part in the Battle of Lowestoft on 13 June 1665. For his achievements he was awarded a knighthood and was appointed an Admiral of the Blue squadron.

In 1673 Allin was created a baronet for his services. In 1678 when the threat of war with France emerged, Allin became commander in chief of the fleet. He died in 1685, and was buried in the parish church at Somerleyton.

SAMUEL MORTON PETO

Samuel Morton Peto, was born in 1809, in Woking, Surrey. As a youth, he was apprenticed as a bricklayer to his uncle Henry Peto, who ran a building firm in London.

When his uncle died in 1830, Peto and his older cousin, Thomas Grissell, went into partnership. The firm of Grissell and Peto built canals and many well-known buildings in London, including the Reform Club, the Oxford & Cambridge Club, the Lyceum, St James's Theatre and arguably the first shopping mall in Britain – Hungerford Market at Charing Cross. They cleared the area for Trafalgar Square, built the square with its fountains and lions and Nelson’s Column. They then took on as sole contractors, the job of building the present day Houses of Parliament followed by the vast infrastructure project of the London brick sewer.

Another project, in 1848, was the Bloomsbury Baptist Chapel, the first Baptist church with spires in London. Tradition has it that the Crown Commissioner was reluctant to lease the land to nonconformists because of their "dull, spire-less architecture". Peto is said to have exclaimed, "A spire, my Lord? We shall have two!" The church had twin spires until 1951, when they were removed as unsafe.

Railway works

In 1834 Peto saw the potential of the newly developing railways and dissolved the connection with his uncle's building firm. He and his cousin Grissell founded a business as an independent railway contractor. His firm's first railway work was to build two stations in Birmingham. Next the firm built its first line of track for the Great Western Railway.

Grissell in 1846 dissolved the partnership.

In 1848 Peto and Edward Betts entered into a partnership and together they were to work on a large number of railway contracts.

In 1854 during the Crimean War Peto and Betts constructed the Grand Crimean Central Railway between Balaklava and Sevastopol to transport supplies to the troops at the front line. The British government recognised Peto for his wartime services; he was made Baronet Peto of Somerleyton Hall.

King Frederick VII of Denmark honoured Peto for building railways which led to a growing export/import trade with the port of Lowestoft.

Peto's arrival to Lowestoft brought about a change in the town's fortunes, which included improving the fishing industry. As a railway contractor, Peto was given the task of building a railway line by the Lowestoft Railway & Harbour Company, connecting the town with Reedham and the city of Norwich, in order to help stimulate further development in the fishing industry, which had begun to take advantage of the Port of Lowestoft since its construction in the 1830s. Its completion had a profound impact on the town's industrial development - not only could its fishing fleets sell products to markets further inland, it also helped to assist in the development of other industries such as engineering, and allowed others to take advantage of the port's boosted trade with the continent. Peto's railway was also essential to establishing Lowestoft as a flourishing seaside holiday resort.

The effect of the arrival of the railway in Beccles was huge. Previously small towns in rural areas were cut off from the rest of the world, travel was slow, uncomfortable, expensive and outside the pockets of most of the population. Its arrival was anticipated with great enthusiasm and it was Peto who brought the railway to Beccles.

The Peto and Betts partnership went into liquidation in 1866 due to the failure of the Overend and Gurney Bank, and partly because of their part in the failure of the London Chatham and Dover Railway.

In 1844, Peto bought Somerleyton Hall in Suffolk for £86,000. (He had been living in Bracondale for the previous three years.) He owned at least 15 manors. He rebuilt the hall with up-to-date amenities, as well as constructing a school and some impressive model houses in the village. For many years he was the largest employer of labour in the entire world.

In 1846, Peto became co-treasurer of the Baptist Missionary Society. From 1855 to March 1867, he was sole treasurer, resigning after personal financial difficulties.

Peto served for 20 years as a Member of Parliament. He was elected a Liberal Member for Norwich in 1847 to 1854, for Finsbury from 1859 to 1865, and for Bristol from 1865 to 1868. During this time he was one of the most prominent figures in public life. He helped to make a guarantee towards the financing of The Great Exhibition of 1851, backing Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace.

After his involvement with the insolvency of the London, Chatham and Dover Railway in 1866, and the failure of the Peto and Betts partnership, Peto's personal reputation as a trustworthy businessman was badly damaged and never fully recovered.

In 1865 he is listed as living at Auchline House in Perthshire.

In 1868, he had to give up his seat in Parliament. He exiled himself to Budapest and tried to promote railways in Russia and Hungary.

When he returned, he tried to launch a small mineral railway in Cornwall but this failed. Peto died in obscurity in 1889.

Peto was big in East Anglia Peto built chapels and supported orphanages and was a very good employer. He treated his navvies with the greatest care and they were the best paid workmen in the country. Peto told the Parliamentary Inquiry into the working condition of railway labourers that as he required his men to shovel 20 tons of earth a day he saw the necessity of paying them well, housing them well when they were in places far from accommodation, and feeding them well.

Peto at first intended to build the Railway Station in Ingate somewhere near the present railway crossing. However responding to a plea by George Fenn who was Mayor at the time Peto agreed to the change to its present, more suitable, position in The Fair Fields. That is what they were, just fields in 1850 while looking east there were no buildings in sight. It was important to Peto to get the local town or village happy with the development and on his side.

Peto bought the site of Station Road and was responsible for its development which was envisaged as a grand entrance to the town from the Railway Station. He then had it parcelled up into lots with various restrictions to the size and quality of houses to be built there, and then sold the plot by auction. The plots sold quickly and houses equally quickly sprang up.

Looking back we have seen some rich who were born with “the silver spoon” in their mouths such as the Dukes of Suffolk and remained rich, some who struggled to keep their wealth with success like the Pastons, some who sprang from the ‘middling sort’ got rich and retained their wealth for example the Crossleys, some like Peto who made a million and lost it and finally the Redes who came from the merchant class and eventually their descendants became aristocrats.